A Perfect Storm

Nothing as simple as a tipping point; I sense a perfect storm may be coming. A year of bad news on the climate front reached a crescendo in December as the Philippines crawled out from under the largest ever typhoon to hit land, Australia witnessed record heat, drought and fires bringing its hottest year on record to an end, and North America had holiday travel plans, the economy and lives disrupted by violent winter weather. Typhoon Haiyan, with sustained winds topping 275 km/hr, claimed 6166 lives in the central Philippines, with 1785 still missing, 28,626 injured and 4.4 million forced from their homes. It was one of their deadliest natural disasters. In Australia, 2013 was already the warmest year on record, and the heat in recent days with inland towns recording highs in excess of 50oC and Brisbane pushing against its all-time records suggests that this summer is likely to be another warm one down under. In North America an erratically oscillating jet stream is bringing successive waves of frigid air well down into the continental USA seriously disrupting air and highway transportation in the eastern half of the continent during the Christmas/New Year season and creating widespread hardship. In the Toronto region, a severe ice storm on 22 December knocking out power to 300,000 homes – some for up to 9 days – coincided with a period of extreme cold to create substantial hardship.

When disparate events come together, the perfect storm which results can open up possibilities for new ways of approaching our problems.

COP19, the 19th meeting of the parties to the Convention on Climate Change, took place in Warsaw in November, and was possibly the least productive of all. It is now very difficult to sustain faith in the idea that a meaningful treaty will be signed in 2015 and in effect by 2020. More or less coinciding with that meeting there was a flurry of articles in the media or on blog sites suggesting that the ‘system was broken’, that national self-interest would always trump needed compromise to bring the majority of the world’s governments to agree on a treaty that would rein in GHG emissions. David Hodgkinson is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Western Australia, whose research focuses on legal issues caused by climate change. Writing in ‘The Conversation’ on 14th October he summarized the seriousness of the climate crisis, pointing out that we have long since passed the point where modest changes by individuals will have any real effect, that a growing consensus is that we will not be able to keep the average warming near, yet alone below, 2oC, and that the focus for policy will have to be on adaptation instead. He brought in the issue of our growing population, and the near-universal belief that raising standards of living across the world to levels approaching those enjoyed in the west is not only ethical but possible in a finite planet, and stated flatly that such a world would be completely unsustainable. He finished a thoroughly depressing commentary by referring to the 6th mass extinction event, and by suggesting we were on the way to our own extinction.

On 21st November, direct from COP19, Democracy Now broadcast an interview with Kevin Anderson and Alice Bows-Larkin, Deputy Director and Researcher respectively at the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research. They are two scientists who believe in walking the walk – they travelled 23 hours by train from Manchester to be at the conference, because neither has flown for about 8 years. The gist of a rather rambling interview was this: that the climate science is very clear in showing we have a mammoth problem on our hands, and the policy community and governments in general still do not seem to understand the urgency to act. Drs. Anderson and Bows-Larkin believe that scientists have an ethical responsibility to campaign, protest, and do whatever else they can when they see that their scientific data and the conclusions drawn from them are not being taken seriously by those people in positions to design and implement mitigation or adaptation. As Anderson said:

“Our role as scientists is to stand up for the analysis that we do. And it if is misused, we should be louder and louder and louder about how it is being misused. But at the moment, there is pressure from both sides for us as scientists to stay quite quiet about this, just to say, ‘Oh, it’s an issue, a problem that we can resolve in the current way of thinking.’ You know, that’s all rubbish. The analysis and the maths are really clear about this now. We need radical change.”

There is a debate within the science community at this time over the extent to which scientists should express their opinions concerning topics for which their research provides scientific insights. A generation ago few scientists would have been politically active, but times are changing. So long as the scientist makes crystal clear when he or she is reporting results and inferences drawn, and when she or he is expressing personal views on policy, I think we have an ethical responsibility to state our views. Other people – politicians, oil company CEOs, Hollywood stars, talk-radio hosts, sundry members of the 1%, and religious leaders – don’t hesitate to express their views; why not scientists. And the view of Anderson and Bow-Larkin is that the science is telling us that global climate change is a far bigger problem than most people seem to realize.

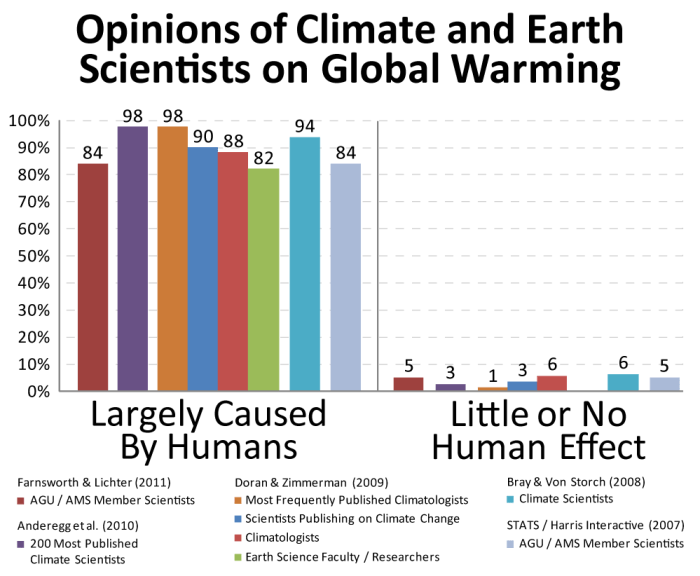

Graph courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

On 8th December, Australian journalist Simon Butler posted on Climateandcapitalism.com a piece in which he first noted some of the observations suggesting climate change is becoming very serious, and then drew a stark conclusion: nothing short of a radical revision of our capitalist system will be sufficient to stem climate change, and we need to act yesterday. In the article he drew attention to the rapid loss of Arctic sea ice, and to recent reports of methane gas escaping from the now warmer Arctic Ocean, and pointed out that these changes have occurred with only a 0.8oC average global warming. We are headed towards a 4oC warming by 2100! He followed these troublesome facts with the news that in 2012 alone, companies spent $674 billion to find and develop new oil, gas and coal deposits. Butler quoted the International Energy Agency’s prediction that global investment in extracting and processing new fossil fuel reserves will add up to a staggering $22.87 trillion between 2012 and 2035, and then quotes a US Energy Analyst Michael Klare, who stated recently that “the energy industry is not investing in any significant way in renewables. Instead, it is pouring its historic profits into new fossil-fuel projects.” Butler’s conclusion? That our capitalist system is a major impediment to making the transition to carbon-neutral energy if we are to combat climate change successfully. While readers need to filter Butler’s arguments bearing in mind his avowed socialism, and the fact that he was writing just a month or so after an election which shifted Australia well to the right, it’s difficult to dismiss his ideas out of hand. The giant energy corporations naturally invest their profits in ventures that will work for them – ventures that bring more of their already-owned reserves to market. In a more centrally planned economy that tendency might be averted, and the corporations required to invest (or more likely the government would taxing and then invest) in carbon-neutral energy sources.

The information on methane releases in the Arctic suggests there is a story to tell. Stay tuned.

Image © arctic-news.blogspot.ca

On 17th December, journalist Dahr Jamail blogged in Truth-out.org about his concerns for the future. This is a very personal account which begins with his discovery of profound changes on the slopes of Mount Rainier over the 16 years since he had last visited it, and ends with reflections on family members who have built vegetable gardens and manage a few chickens, and on what his own life will be like (he is 45) if he lives to see a 3.5oC warming. In between he also dwells on changes in the Arctic and on how so many scientists are talking about many aspects of climate change that they believe to be extreme already, or moving rapidly in that direction. And he notes the general lack of progress to solve these problems.

Canadian journalist Steve DaSilva published his interview with John Bellamy Foster on Monthly Review’s webzine, MRzine, on 18th December. Foster, editor of Monthly Review and a Professor of Sociology at University of Oregon, is a self-described Marxist ecologist. The interview is lengthy but hits the same general themes – the climate crisis is very serious, there is little movement towards fixing it, fixing it is going to require radical transformation of our economic system, and the existing political system (small p) is blocking any change at every turn. It includes some interesting observations on the role of Idle-No-More, Nimbyism, opposition to pipelines, and the trillionth tonne of CO2. The latter is a reference to the cumulative total of CO2 that can be put into the atmosphere that is still compatible with a temperature rise of <2oC. Calculations by IPCC and others suggest that anthropogenic contributions since the start of the industrial age must not exceed a trillion metric tonnes of CO2 equivalents, and further, that on our current trajectory we will deliver this trillionth tonne in 2040. One point that intrigued me was Foster’s assertion that the argument that we cannot build support for reducing emissions by ‘preaching doom and gloom’ is an argument developed by the political right, rather than by the political left. I’ve heard this articulated frequently by people who were concerned to find effective ways of conveying the message about the seriousness of climate change. Maybe they are victims of another piece of deliberate obfuscation by the right? Or maybe Foster is too wrapped up in his Marxist dialectical materialism to see clearly where arguments come from?

In any event, these are just a small sample of what is currently appearing on the web. That several of them mentioned Arctic releases of methane has caused me to see what I can find out about that topic over the next month or so – I’d like to see some peer-reviewed literature before getting too excited about claims on blogs. Still, putting Arctic methane aside, these articles share a common message: the environmental crisis is far more serious than most people realize, despite this little if any progress is being made towards remedies, and there are features of prevailing economic systems that make it very difficult (most would claim impossible) to make the needed changes quickly enough. Meanwhile, the energy corporations continue to invest heavily in the search for ever more fossil fuel. All of which brings me back to fossil fuel, tar sands, Keystone XL, Northern Gateway, other pipelines, and Canada’s performance on the climate change stage.

The 90 ‘Carbon Majors’

Oil refining is big business. This is a BP plant in Texas City TX

I’ll ease into comments on Canada gently, by first looking at a recent article by Richard Heede, a founding member of the non-profit Climate Accountability Institute, in Snowmass, Colorado. Published on-line on 22nd November in Climate Change, Heede’s article takes a fresh look at who is responsible for the anthropogenic GHG emissions since 1854. The impetus for doing this article arose from a 2012 workshop organized by the Climate Accountability Institute and the Union of Concerned Scientists, and held at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in June 2012. That workshop brought together a group of natural and social scientists, legal scholars and public opinion experts to consider whether the story of tobacco provided any direction for how to establish accountability for causing climate change. As one participant, climate scientist Myles Allen said, “Why should taxpayers pay for adaptation to climate change?” (Or put another way, why should citizens of tiny countries such as the Maldives or Vanuatu pay to relocate when their countries are eliminated by sea level rise that they certainly did not cause?)

In his Climate Change article, Heede begins with the observation that the UNFCCC has focused attention on the role of nation-states in causing climate change. It is obvious that citizens of developed nations have benefitted most from the extraction and use of fossil fuels up till now, and therefore have a much greater degree of responsibility for causing this problem than do less wealthy nations. This has pitted the haves against the have-nots in a long-running series of negotiations that have yet to achieve any significant lessening of the rate of GHG emissions. An alternative nation-based way of attributing responsibility would be to look at the lands from which fossil fuels have been extracted (these would include most of the have nations and some of the less developed nations as well. But neither of these approaches really goes to the heart of who it is that has benefitted personally at the expense of our shared environment. Heede has combed through data including company annual reports and governmental records to trace the ownership of reserves brought to market since 1854. He has examined the fossil fuel and cement manufacturing activities of the 50 leading investor-owned, 31 state-owned, and 9 nation-state producers of oil, natural gas, coal, and cement from 1854 to 2010, and found that these 90 business entities have collectively been responsible for releases of 914 Gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) as industrial CO2 and methane—63 % of cumulative worldwide emissions. His data include the carbon content of marketed hydrocarbon fuels (subtracting for non-energy use), process CO2 from cement manufacture, the CO2 released directly from venting, flaring and own fuel use, as well as fugitive and vented methane. The investor-owned entities are responsible for 315 GtCO2e, state-owned entities for 288 GtCO2e, and nation-states for 312 GtCO2e. Half of these emissions have occurred since 1986. (As Heede explains, his estimates are biased downwards for several unavoidable reasons.) What is scary to contemplate is that these same 90 ‘carbon majors’ possess the bulk of proven reserves, and IEA has already stated that the world cannot afford to bring more than 1/3 of these remaining reserves to market if we want to retain a sustainable environment. How are we to stop these powerful corporations marketing their reserves?

In causing 63% of our global carbon pollution, these 90 entities have made substantial profits. It might be appropriate therefore to work with these ‘carbon majors’ to find ways for them to invest something approaching 63% of the cost that the global community must now bear to deal with the consequences. In discussing Heede’s paper, The Guardian quotes Heede as saying,

“There are thousands of oil, gas and coal producers in the world. But the decision makers, the CEOs, or the ministers of coal and oil if you narrow it down to just one person, they could all fit on a Greyhound bus or two.”

The Guardian also quotes Michael Mann, who points out that since fossil fuels can be ‘fingerprinted’, it should be possible to track all future fuels back to their source, unambiguously assigning responsibility for polluting to the producer entity. We may finally have a tool which can be used to apply the “polluter pays” principle in the climate change arena.

These 90 entities are headquartered in 43 different nations, and extract hydrocarbons in all hydrocarbon provinces of the world, selling their products to every nation on the planet. Several of them have been active in the sowing of disinformation and doubt about climate change, and it would be fitting to see them spending money on the clean-up that has to take place. Would such a move impact the global economy? Absolutely, but we have known all along that having our cake and eating it too has never been an option.

Canada’s Failing Policy on Economics, Energy and Environment

And so to Canada. Stephen Harper had a bad year in 2013 for reasons not to do with the energy file. 2014 may be the year in which his energy policy finally starts to unravel. Canada’s national economic policy has featured a focus on exploitation of the tar sands as the prime engine to keep our economy strong. Fossil fuel companies were happy to go along with a government that was soft on regulation and a real cheerleader for plans to triple production, but this history of cozy relations with the hydrocarbon sector has begun to bite the government, and the economic reasons for a rapid ramp-up in production are no longer there, if they ever were. Growth in production of unconventional (fracked) oil and gas in the US, the likelihood of restored production in Iran, and the lessening of demand growth due to the faltering world economy, and advances in energy efficiency all act to lower fuel prices. Alberta’s dirty oil carries a significant price discount at refineries when other sources of easier-to-refine product are readily available. As a consequence, even if Keystone XL and Northern Gateway were both already in place, the economic justification for ramping up production has lessened. It may well lessen further in future months, but a number of companies have announced scale-backs or cancellations in the tar sands in recent months. Nor is it a safe bet that either pipeline will ever be built. Chantel Hébert, writing in The Star, advises that Northern Gateway may be a battle that the Harper government would be wise to avoid in the run-up to an election, because the opposition to this pipeline is deeper and broader than to almost any other fossil fuel proposal on the table. And that is despite the go-ahead issued by the National Energy Board late last year. In the US, approval of Keystone XL has become heavily politicized and that country is now well into its next election cycle also. With its broader economy finally starting to improve, the US does not need the few jobs the pipeline would generate, and the refineries are not crying out for product.

Cartoon © Ecosanity.org

With hindsight, Canada probably made a crucial mistake many years ago when it did not insist on building a comprehensive refining industry in Alberta in conjunction with development of the tar sands. Canadians would have reaped far greater benefits per tonne of carbon from the tar sands oil (in high-value jobs and an advanced chemical processing industry) if refined products had been exported, but, of course, the corporations were not in favor of investing in the expensive infrastructure when they had refineries sitting idle on the Texan coast, and Canadian and Albertan governments wanted the tax and royalty income from “digging it up and shipping it out”. With hindsight, Canada certainly made a crucial mistake when it permitted governments to become cheerleaders of the industry instead of guardians of the environment, and while the Harper government has been the most willing to be a lap dog to the ‘carbon majors’, earlier governments must bear some blame as well. The Canadian public has not been served well by a myopic focus on quick jobs and tax revenue.

Still, regardless of past mistakes, we Canadians are here, now, with a messy industry polluting Alberta and places downstream to the Arctic, an industry that could easily collapse as the price of oil declines, and a climate policy among the worst in the developed world. Daniel Kessler has an article in Grist that points to the extent to which our environmental and science policies have been hijacked by the effort to smooth the way for our friends in the fossil fuel industry. Given that proven reserves in the tar sands equal about 17% of the available remaining carbon budget (until we reach that trillionth tonne of emissions) compatible with a 2oC warmer world, it is inconceivable that those reserves will ever be brought to market, so Mr. Harper needs to start planning for a new economic strategy. (It’s inconceivable because even if governments and corporations remain willing, the deteriorating global environment will prove so disruptive that the economy which that fuel is being produced for will simply not be there to purchase it.) It’s time certain politicians and business leaders woke up.

The Financial Post has an interesting overview of prospects for the tar sands industry in 2014. The author is clearly clinging to the idea that there is lots of money to be made from exploiting these resources, but he sets out a number of difficulties that loom this year.

What I am suggesting, of course, is that conditions are conspiring to damping economic success in the tar sands, and that 2014 could be the year which sees us begin to move back towards a more balanced economic policy, less dependent on one sector, and a much more responsible environmental policy. This change, which will not be completed within the year, will impose serious drags on our economy, but we have been living in a fool’s paradise if we believed we could go on ignoring the accumulating signs of our folly in trying to become a petrostate. The good news is we remain a country with significant human capital, and the wealth to weather a transition towards a more sustainable path. Will the Harper government lead the way? Not likely, but politicians can be remarkably adaptable. Let’s wait and see.

After the Perfect Storm, a New Day

I am going to end on two positive notes, because this perfect storm of changed perceptions does represent an opportunity. First, Ontario is going to shut down the Nanticoke Generating Station during 2014, becoming the first jurisdiction in North America to totally remove coal from its electricity generating systems. In 10 years, Ontario has reduced coal from producing 25% of its electricity to zero, proving that it IS POSSIBLE to transition away from use of fossil fuels. Yes, it has cost, and will cost, but paying the true cost of energy is what citizens should do, so long as the poor are provided some relief.

Second, Stephen Scharper, an Associate Professor of Environment and Religious Studies at the University of Toronto, writing his regular monthly column in The Star, provides some uplifting words concerning Bolivia’s Pachamama law, which draws heavily on indigenous beliefs about the land, and is among the first to give nature legal rights, specifically the rights to life, regeneration, biodiversity, water, clean air, balance and restoration. This law will reorient Bolivia’s economy, and Canadians could well take a look at it. Scharper also praises Pope Francis’s focus on the environment in his recent Christmas homily. I rarely look to the Vatican for leadership on anything much, but this Pope may be something new: a papal portion of a magnificent and perfect storm out of which we can perhaps begin to see some real movement towards confronting our environmental challenges more creatively. I hope so.

Nature as Pachamama. Graphic © Canciones Temáticas

Hear! Hear!

so … it IS possible to tell the truth and be positive 🙂

David, yes, its possible. But I have to be in a really up mood to manage it.

Comments are closed.